ADVENTUROUS TEACHING STARTS HERE.

Cultivating Critical Thinkers: My Approach to Teaching Literature

As an educator, I've always been passionate about instilling critical thinking skills in my students. It's a topic that I recently had the opportunity to reflect on during a professional development session, and I want to share with you the insights and strategies that I believe are essential for deep engagement in the classroom.

Planning a Novel Unit Reading Calendar

The art of pacing out the reading during a novel unit can be tricky, so we’re going to take some time today to talk through the process. Whether you’re teaching a classic or a contemporary YA title, there are special considerations to be made for the design of your calendar and how we backwards plan for ELA. Let’s jump in!

Does Taylor Swift have a place in the ELA Classroom?

And here's the thing: if your students are talking about Taylor, then so should you. This is an open door into engagement and skill building that is not to be missed. Here are three ways to pull the power of Taylor into your classroom and spike engagement among your students…

5 Ways to Look at the Magic of Clarisse in your Fahrenheit 451 Unit

Now, more than ever, we need to have Fahrenheit 451 in front of our students. From the new onset of AI technology to the daily threats of our intellectual and academic freedom, Fahrenheit provides windows, mirrors, and doors into our present and our future. While Montag’s transformation, the working symbolism, and general dystopian world-building are all incredibly important pieces to focus on, I’d like to argue that it’s possible we need Clarisse McClellan the most.

20 Speeches and Text for Introducing SPACE CAT and Rhetorical Analysis

During the introductory phases of teaching rhetorical analysis, you need to start off with texts that are approachable and teachable. This helps to build student confidence as the texts get harder and harder each year. Here are 20 places where you can start that journey confidently!

Teaching Short Story Units with a Modern, Contemporary Twist in Secondary ELA

If you’ve ever found yourself searching the internet for “contemporary short stories” or “modern short stories” because you’re tired of teaching the same classic stories over and over again, I have THE HACK to change everything for you!

How to Create Book Club Magic Using Essential Questions {Part Two}

Lackluster literature circles? Boring book clubs? The remedy: lose traditional “role” sheets, declare freedom from organization by topic or genre, and build essential question-focused literature circles or book clubs instead. An EQ as the throughline for your lit circle/book club unit kicks up the impact that comes from having kids talk about what they read in a way that just does not happen with any other method. Here’s why…

How to Create Book Club Magic Using Essential Questions {Part One}

Lackluster literature circles? Boring book clubs? The remedy: lose traditional “role” sheets, declare freedom from organization by topic or genre, and build essential question-focused literature circles or book clubs instead. An EQ as the throughline for your lit circle/book club unit kicks up the impact that comes from having kids talk about what they read in a way that just does not happen with any other method. Here’s why…

Teaching Rhetorical Analysis: Using Film Clips and Songs to Get Started with SPACE CAT

Try beginning your rhetorical analysis lessons by focusing on the rhetorical situation before heading into deeper analysis. When you’re ready, dig in using SPACE CAT and a great song from a musical that has a premise and an argument to examine. Here’s what we’ve done in my class using “Mother Knows Best” from Tangled.

Three Myths about Close Reading

Close reading is often confused or made synonymous with things it most definitely is not, making it seem too scary to even approach. Maybe you’ve tried it, hit a wall of frustration and abandoned-ship. Well, it’s time to replace frustration, uncertainty and fear with the truth, and bust three common myths of close reading.

How to Throw a Gatsby Party as PreReading Strategy

Teaching The Great Gatsby is a massive task, but setting up students during prereading is a critical moment to help them feel successful as they’re tackling the novel from the start. Here’s how to use a Gatsby Party as a stations activity that helps students get to know each of the major characters in the novel.

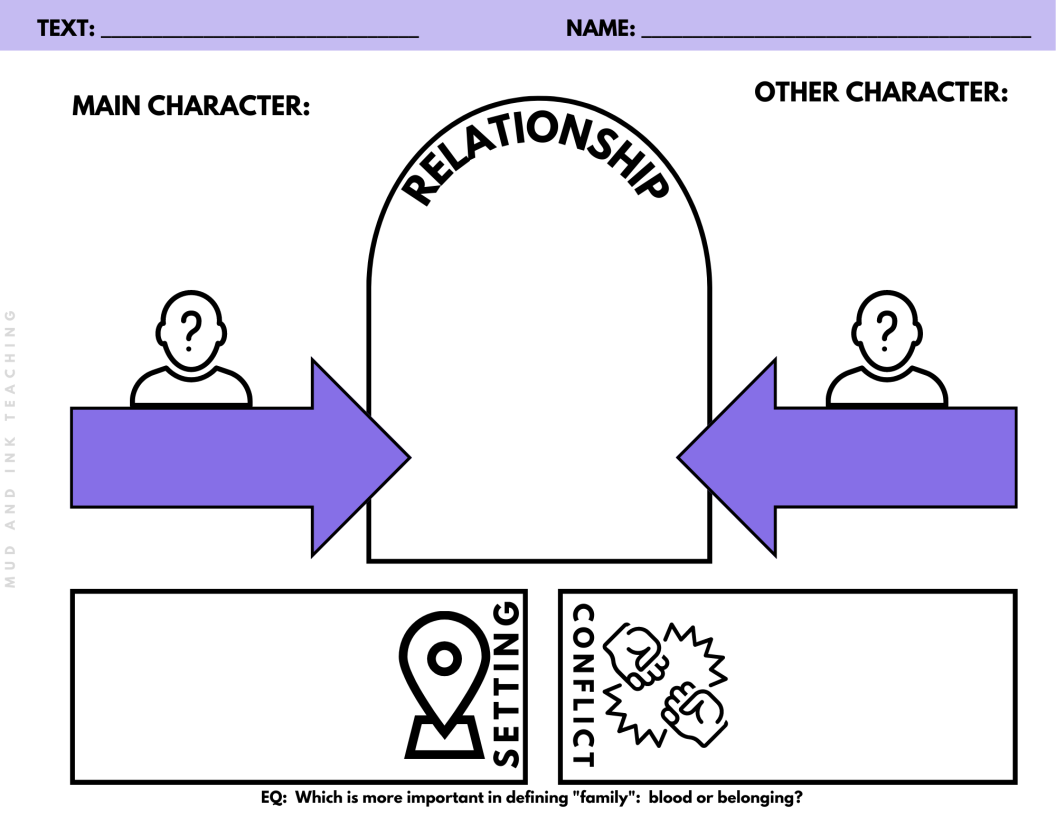

Unit Makeover: The Short Story Unit in Secondary ELA

Short story units have the potential to deeply inspire and impact learning with students, but if the approach is disjointed or lacking any sort of alignment, these units can feel like flops. Here are the ways that I craft meaningful, engaging, and interesting units to highlight the short stories that we love (and a few more that we should add to the rotation!)

3 Habits for Happy, Powerful Teachers

Teachers can have happiness and power over their own lives, but it all starts with creating good habits. These are three habits that changed everything about my teaching career.

Helping Students do Hard Things in ELA

Rigor is not the same thing as busy work. Pushing students and challenging students to do their best work and to excel past their wildest dreams takes concentration, planning, and intention. Here are 12 ways to support students as you challenge them every step of the way.

4 Authors, Activists and Artists to Highlight During Black History Month

Here are four authors and artists that deserve a spotlight any time of year, but especially during Black History Month. Each has a speech, story, or TED Talk that you can share with students alongside a wide variety of units.

Three Reasons You Should be Teaching A Thousand Splendid Suns

If you have a world literature course, or any upperclassman English course for that matter, A Thousand Splendid Suns should be in your curriculum. Full stop. This is by far and away one of my personal and my students’ favorite novels and if you’re not teaching it, you’re missing out. There are so many things about this novel unit that are perfect for skill-building and ripe for deep, meaningful discussion, but if I had to boil it down to my top three, then here they are…

5 Common Mistakes Teachers Make When Teaching Figurative Language

Raise your hand if the first unit of your school year is a short story unit with figurative language terminology review? Yes? This is unit one in thousands of English classrooms and this makes me wonder…if they’ve done this so many times, why aren’t they experts? How is it that by unit 2, the next time we encounter an example of personification, they’ve forgotten the term altogether?

The thought process here is logical: provide terms, provide definitions, provide examples, practice, practice practice = learning has succeeded. But we see this doesn’t actually happen. So what’s not working?

30 Poems to Teach Using The Big Six

I love this poem. I love the imagery, the title, the metaphor, but most of all, I love how teachable it is. The poem has a great deal of mystery and room for debatable discussions about author’s intent, but it’s also accessible to students who might feel intimidated by poetry - or even just intimidated by language.

That was the goal I had in mind while making this list: I wanted to find poems that were challenging and worth discussing in class, but also poems that could be tackled by students in one or two class periods. As a guide, I used The Big Six as my foundational analysis tool . If you’ve never used it, get on board!