ADVENTUROUS TEACHING STARTS HERE.

5 Ways to Look at the Magic of Clarisse in your Fahrenheit 451 Unit

Now, more than ever, we need to have Fahrenheit 451 in front of our students. From the new onset of AI technology to the daily threats of our intellectual and academic freedom, Fahrenheit provides windows, mirrors, and doors into our present and our future. While Montag’s transformation, the working symbolism, and general dystopian world-building are all incredibly important pieces to focus on, I’d like to argue that it’s possible we need Clarisse McClellan the most.

55+ Books for Your Next American Dream Unit for High School ELA

One of my favorite units to teach is a unit that focuses on the American Dream. It’s the perfect way to hone in on complex characterization and the layers of complexity are widely accommodating for skill level. Whether you’re building the unit to teach as a whole class novel unit or as a literature circles unit, this book list is here to save you time and energy in narrowing down the search.

Teaching Short Story Units with a Modern, Contemporary Twist in Secondary ELA

If you’ve ever found yourself searching the internet for “contemporary short stories” or “modern short stories” because you’re tired of teaching the same classic stories over and over again, I have THE HACK to change everything for you!

How to Create Book Club Magic Using Essential Questions {Part Two}

Lackluster literature circles? Boring book clubs? The remedy: lose traditional “role” sheets, declare freedom from organization by topic or genre, and build essential question-focused literature circles or book clubs instead. An EQ as the throughline for your lit circle/book club unit kicks up the impact that comes from having kids talk about what they read in a way that just does not happen with any other method. Here’s why…

How to Create Book Club Magic Using Essential Questions {Part One}

Lackluster literature circles? Boring book clubs? The remedy: lose traditional “role” sheets, declare freedom from organization by topic or genre, and build essential question-focused literature circles or book clubs instead. An EQ as the throughline for your lit circle/book club unit kicks up the impact that comes from having kids talk about what they read in a way that just does not happen with any other method. Here’s why…

Books for Your Next Unit on Relationships for Middle and High School ELA

One of my favorite units to teach is a unit that focuses on relationships. It’s the perfect way to hone in on complex characterization and the layers of complexity are widely accommodating for skill level. Whether you’re building the unit to teach as a whole class novel unit or as a literature circles unit, this book list is here to save you time and energy in narrowing down the search.

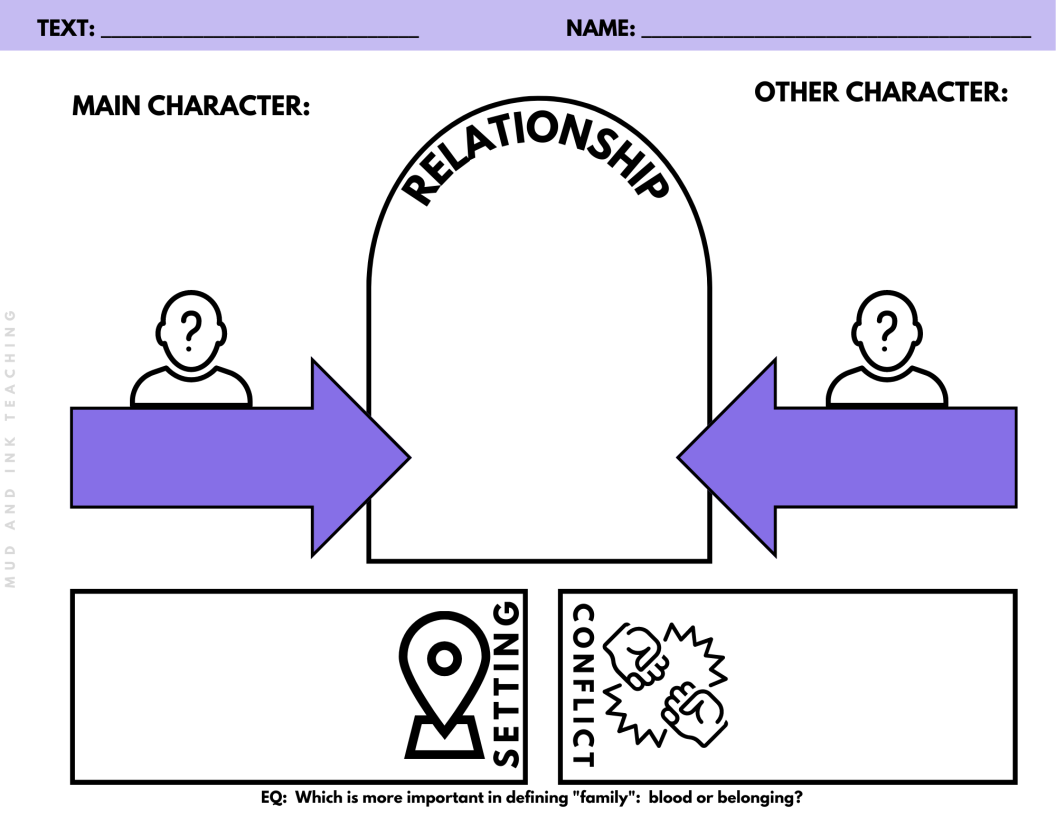

Unit Makeover: The Short Story Unit in Secondary ELA

Short story units have the potential to deeply inspire and impact learning with students, but if the approach is disjointed or lacking any sort of alignment, these units can feel like flops. Here are the ways that I craft meaningful, engaging, and interesting units to highlight the short stories that we love (and a few more that we should add to the rotation!)

Helping Students do Hard Things in ELA

Rigor is not the same thing as busy work. Pushing students and challenging students to do their best work and to excel past their wildest dreams takes concentration, planning, and intention. Here are 12 ways to support students as you challenge them every step of the way.

Must-Try Essential Questions for your next Shakespeare Unit

Essential Questions are the backbone of inquiry-based teaching and learning, but writing them and using them can be challenging in a Shakespeare unit. Here are my favorite essential questions to use in some of the most popular plays that we teach in the classroom and how to move forward using them.

12 Ideas for Teaching American Lit

These are 12 fresh, new ideas for shaking up your American Literature curriculum: from essential questions to literary food trucks, take these ideas to change up how you’ve done things in the past.

How to Write Essential Questions that Engage Students

For a long time, English teachers have been teaching in three very specific ways: novel-based, skill-based, and theme-based units. This was how I started my career, too. But then, I learned the power of Essential Questions.

The Best Essay My Students Ever Wrote

You guys. This is the first time in over a decade of teaching that I’ve gone through a stack of papers saying, “Yes! Yes! YESSS!!!!” I’m so proud of what’s been accomplished that I’m just dying to share with you how to make this happen in your own classroom.

How To Build A New Novel Unit From Scratch

After teaching for ten years and then switching schools, I was very quickly reminded of how much work goes into writing curriculum from scratch. For a long time, I was in a happy place of continual revision of curriculum that I liked, but was tweaking here and there for relevance, rigor, and for fun.

Now? It’s the Wild West. It’s intergalactic chaos. It’s constant guessing and unpredictability. All that aside, however, it’s also invigorating and exciting. I would call myself “a curriculum person” because this kind of blank slate challenges me in a way that sparks joy in my life, despite the chaos, so I’d like to share with you how to most easily navigate through a first attempt at writing and implementing a new curriculum for a new novel in your secondary ELA classroom.